The Science Behind Green Paw

When we talk about sustainability in veterinary medicine, it is easy for the conversation to drift toward values, intentions, or isolated examples of “doing better.” Those conversations matter, but they are not enough. If sustainability is going to become part of routine veterinary practice, it must be grounded in evidence, shaped by the realities of clinics, and flexible enough to work across regions, practice types, and business models.

That need for credible, practical guidance is what motivated our recent paper, Environmental sustainability in veterinary clinics: best practices for the United States and Canada. This work forms the scientific backbone of the Green Paw Certification.

The paper was led by Colorado State University ACVPM residents Drs. Caroline Kern-Allely and Danni Scott, with close collaboration from Dr. Katie Clow at the University of Guelph, who also serves as a Director of the Veterinary Sustainability Alliance, and myself. Together, we set out to answer a simple but critical question: What does evidence-based environmental sustainability actually look like for veterinary clinics in the U.S. and Canada?

Why This Work Was Needed

Veterinary professionals are increasingly motivated to reduce the environmental impacts of clinical practice. At the same time, many clinics lack clear, trusted guidance on where to start or how to prioritize actions. While sustainability frameworks are well established in human healthcare, comparable resources tailored to veterinary practice in North America have been limited.

Rather than reinventing the wheel, our goal was to identify what already exists, evaluate it rigorously, and adapt it to the realities of veterinary clinics. This project combined a comprehensive gray literature review with a structured expert review process. Our team drew from both veterinary and human healthcare sustainability resources, then worked with a panel of subject matter experts using a modified Delphi method to refine, prioritize, and contextualize each action.

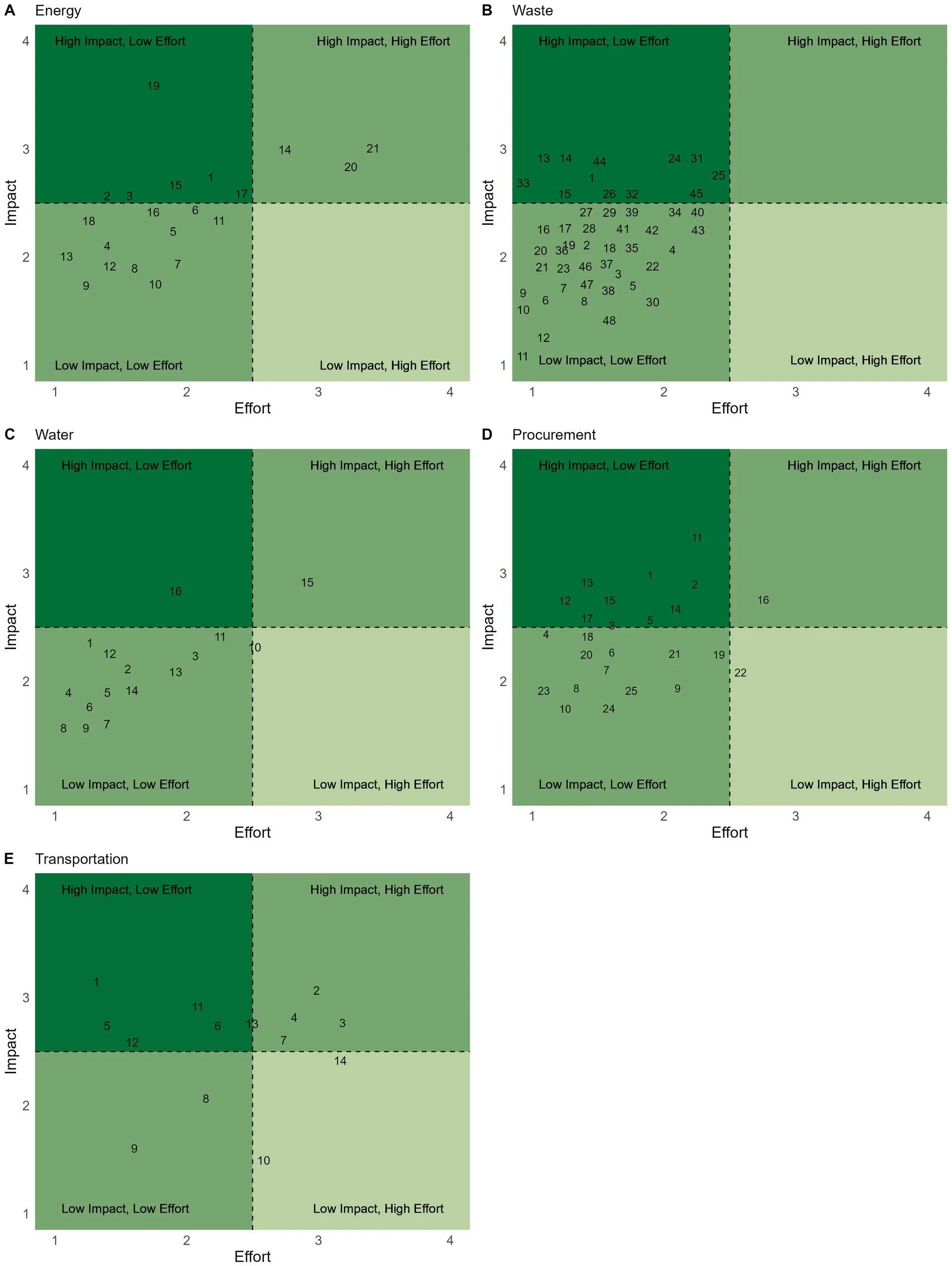

The result was a set of 199 evidence-informed actions, organized into a practical framework that clinics can adapt based on their size, location, and capacity. Actions were evaluated not only for their potential environmental impact, but also for the effort required to implement them (see figure). This dual lens matters. Sustainability efforts succeed when they balance ambitious, high-impact changes with achievable early wins that build momentum.

Figure 2 from Kern-Allely C et al. Environmental sustainability in veterinary clinics: best practices for the United States and Canada. Frontiers in Veterinary Science (2025).Sustainability actions under the Clinic tier are plotted based on their average effort (x-axis) and impact (y-axis) scores for the categories Energy(A), Waste(B), Water(C), Procurement(D), and Transportation(E). Each number corresponds to the actions listed in Tables 6–10, by referenced category.

One of the most important conclusions of the paper is that there is no single “right” way for a clinic to be sustainable. Geography, infrastructure, regulations, and resources vary widely across the U.S. and Canada. What clinics need is a flexible roadmap that allows them to start where they are and progress over time.

That insight directly shaped Green Paw. By grounding Green Paw in peer-reviewed science, VSA is signaling that sustainability in veterinary practice is not about trends or optics. It is about informed decision-making and continuous improvement.

The Frontiers paper provides the evidence. Green Paw provides the structure. Together, they offer a credible path forward for clinics that want to be part of the solution.